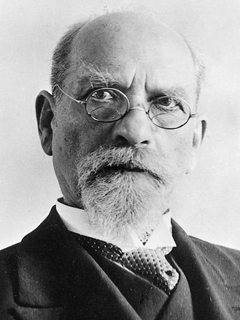

Husserl's conception of "the grammatical" and contemporary linguistics

pp. 137-161

in: Mohanty (ed), Readings on Edmund Husserl's Logical Investigations, The Hague, Nijhoff, 1977Abstract

Since the Middle Ages philosophers have periodically made proposals for a universal a priori grammar, frequently suggesting that such a grammar be considered as a branch or an application of formal logic. These researches have never progressed very far, not even during the period when grammarians were themselves primarily logicians. In the modern period, since scientific linguistics has vindicated its own independence of logic and philosophy, philosophical proposals of this kind have fallen into "scientific" disrepute. Thus, Edmund Husserl's project for a "pure logical grammar" — which is probably the most recent full-scale proposal in this area from the side of philosophy — has fallen upon deaf ears. But now, within the past decade, Noam Chomsky has begun to propose, from the side of linguistics itself, a program for the study of grammar which, if it were to succeed, might seem to justify the earlier intuitions of rationalistic philosophy and to give a new grounding to its ancient quest. Might it not be, after all, that what was needed was a more sophisticated development of grammatical studies themselves before such a proposal could be sufficiently clarified to be prosecuted with any confidence?