Bayesian induction and statistical inference

pp. 103-121

in: Gonzalo Munvar (ed), Spanish studies in the philosophy of science, Berlin, Springer, 1996Abstract

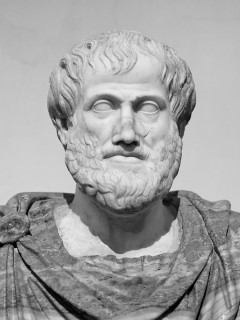

For more than two thousand years the question of how to achieve valid knowledge of the world has concerned Western epistemologists. From Aristotle, in the 4th Century B.C., until the contemporary theoreticians of induction, including both frequentist and Bayesian statisticians, the belief in the inductive character of the scientific method has been embodied in Western culture, with very few exceptions. Therefore Karl Popper (1979), one of the rare philosophers of science who, as David Hume in the first half of the Eighteenth Century, did not believe in induction as the "glory of science', rightly called the problem of induction one of the two fundamental problems of epistemology; the other one being the problem of demarcation between genuine science and pseudoscience.